বাংলাভাষা ও বাঙালি চরিত্র : ১

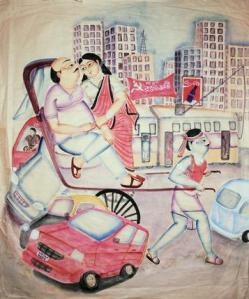

অনেক সময় দেখা যায় সংস্কৃত শব্দ বাংলায় রূপান্তরিত হয়ে এক প্রকার বিকৃত ভাব প্রকাশ করে। কেমন একরকম ইতর বর্বর আকার ধারণ করে। “ঘৃণা’ শব্দের মধ্যে একটা মানসিক ভাব আছে। Aversion, indignation, contempt প্রভৃতি ইংরাজি শব্দ বিভিন্ন স্থল অনুসারে “ঘৃণা’র প্রতিশব্দ স্বরূপে ব্যবহৃত হইতে পারে। কিন্তু “ঘেন্না’ বললেই নাকের কাছে একটা দুর্গন্ধ, চোখের সামনে একটা বীভৎস দৃশ্য, গায়ের কাছাকাছি একটা মলিন অস্পৃশ্য বস্তু কল্পনায় উদিত হয়। সংস্কৃত “প্রীতি’ শব্দের মধ্যে একটা বিমল উদার মানসিক ভাব নিহিত আছে। কিন্তু বাংলা “পিরিতি’ শব্দের মধ্যে সেই বিশুদ্ধ ভাবটুকু নাই। বাংলায় “স্বামী’ “স্ত্রী’র সাধারণ প্রচলিত প্রতিশব্দ ভদ্রসমাজে উচ্চারণ করিতে লজ্জা বোধ হয়। “ভর্তা’ এবং তাহার বাংলা রূপান্তর তুলনা করিয়া দেখিলেই এ কথা স্পষ্ট হইবে। আমার বোধ হয় সংস্কৃত ভাষায় “লজ্জা’ বলিলে যতটা ভাব প্রকাশ করে, বাংলায় “লজ্জা’ ততটা করে না। বাংলায় “লজ্জা’ এক প্রকার প্রথাগত বাহ্য লজ্জা, তাহা modesty নহে। তাহা হ্রী নহে। লজ্জার সহিত শ্রীর সহিত একটা যোগ আছে, বাংলা ভাষায় তাহা নাই। সৌন্দর্যের প্রতি স্বাভাবিক লক্ষ্য থাকিলে আচারে ব্যবহারে, ভাবভঙ্গিতে ভাষায় কণ্ঠস্বরে সাজসজ্জায় একটি সামঞ্জস্যপূর্ণ সংযম আসিয়া পড়ে। বাংলায় লজ্জা বলিতে যাহা বুঝায় তাহা সম্পূর্ণ স্বতন্ত্র, তাহাতে বরঞ্চ আচার-ব্যবহারের সামঞ্জস্য নষ্ট করে, একটা বাড়াবাড়ি আসিয়া সৌন্দর্যের ব্যাঘাত করে। তাহা শরীর-মনের সুশোভন সংযম নহে, তাহার অনেকটা কেবলমাত্র শারীরিক অভিভূতি।

গল্প আছে– বিদ্যাসাগর মহাশয় বলেন উলোয় শিব গড়িতে বাঁদর হইয়া দাঁড়ায়, তেমনি বাংলার মাটির বাঁদর গড়িবার দিকে একটু বিশেষ প্রবণতা আছে। লক্ষ্য শিব এবং পরিণাম বাঁদর ইহা অনেক স্থলেই দেখা যায়। উদার প্রেমের ধর্ম বৈষ্ণব ধর্ম বাংলাদেশে দেখিতে দেখিতে কেমন হইয়া দাঁড়াইল। একটা বৃহৎ ভাবকে জন্ম দিতে যেমন প্রবল মানসিক বীর্যের আবশ্যক, তাহাকে পোষণ করিয়া রাখিতেও সেইরূপ বীর্যের আবশ্যক। আলস্য এবং জড়তা যেখানে জাতীয় স্বভাব, সেখানে বৃহৎ ভাব দেখিতে দেখিতে বিকৃত হইয়া যায়। তাহাকে বুঝিবার, তাহাকে রক্ষা করিবার এবং তাহার মধ্যে প্রাণসঞ্চার করিয়া দিবার উদ্যম নাই।

আমাদের দেশে সকল জিনিসই যেন এক প্রকার slang হইয়া আসে। আমার তাই এক-একবার ভয় হয় পাছে ইংরাজদের বড়ো ভাব বড়ো কথা আমাদের দেশে ক্রমে সেইরূপ অনার্য ভাব ধারণ করে। দেখিয়াছি বাংলায় অনেকগুলি গানের সুর কেমন দেখিতে দেখিতে ইতর হইয়া যায়। আমার বোধ হয় সভ্যদেশে যে যে সুর সর্বসাধারণের মধ্যে প্রচলিত, তাহার মধ্যে একটা গভীরতা আছে, তাহা তাহাদের national air, তাহাতে তাহাদের জাতীয় আবেগ পরিপূর্ণভাবে ব্যক্ত হয়। যথা Home Sweet Home, Auld lang Syne–, বাংলাদেশে সেরূপ সুর কোথায়? এখানকার সাধারণ-প্রচলিত সুরের মধ্যে গাম্ভীর্য নাই, স্থায়িত্ব নাই, ব্যাপকতা নাই। সেইজন্য তাহার কোনোটাকেই national air বলা যায় না। হিন্দুস্থানীতে যে-সকল খাম্বাজ ঝিঁঝিট কাফি প্রভৃতি রাগিণীতে শোভন ভদ্রভাব লক্ষিত হয়, বাংলায় সেই রাগিণীই কেমন কুৎসিত আকার ধারণ করিয়া “বড় লজ্জা করে পাড়ায় যেতে’ “কেন বল সখি বিধুমুখী’ “একে অবলা সরলা’ প্রভৃতি গানে পরিণত হইয়াছে।

কেবল তাহাই নহে, আমাদের এক-একবার মনে হয় হিন্দুস্থানী এবং বাংলার উচ্চারণের মধ্যে এই ভদ্র এবং বর্বর ভাবের প্রভেদ লক্ষিত হয়। হিন্দুস্থানী গান বাংলায় ভাঙিতে গেলেই তাহা ধরা পড়ে। সুর তাল অবিকল রক্ষিত হইয়াও অনেক সময় বাংলা গান কেমন “রোথো’ রকম শুনিতে হয়। হিন্দুস্থানীর polite “আ’ উচ্চারণ বাংলায় vulgar “অ’ উচ্চারণে পরিণত হইয়া এই ভাবান্তর সংঘটন করে। “আ’ উচ্চারণের মধ্যে একটি বেশ নির্লিপ্ত ভদ্র suggestive ভাব আছে, আর “অ’ উচ্চারণ নিতান্ত গা-ঘেঁষা সংকীর্ণ এবং দরিদ্র। কাশীর সংস্কৃত উচ্চারণ শুনিলে এই প্রভেদ সহজেই উপলব্ধি হয়।

উপরের প্যারাগ্রাফে এক স্থলে commonplace শব্দ বাংলায় ব্যক্ত করিতে গিয়া “রোথো’ শব্দ ব্যবহার করিয়াছি। কিন্তু উক্ত শব্দ ব্যবহার করিতে কেমন কুণ্ঠিত বোধ করিতেছিলাম। সকল ভাষাতেই গ্রাম্য ইতর শব্দ আছে। কিন্তু দেখিয়াছি বাংলায় বিশেষ ভাবপ্রকাশক শব্দমাত্রই গ্রাম্য। তাহাতে ভাব ছবির মতো ব্যক্ত করে বটে কিন্তু সেইসঙ্গে আরো একটা কী করে যাহা সংকোচজনক। জলভরন শব্দ বাংলায় ব্যক্ত করিতে হইলে হয় “মুচ্কে হাসি’ নয় “ঈষদ্ধাস্য’ বলিতে হইবে। কিন্তু “মুচ্কে হাসি’ সাধারণত মনের মধ্যে যে ছবি আনয়ন করে তাহা বিশুদ্ধ smile নহে, ঈষদ্ধাস্য কোনো ছবি আনয়ন করে কি না সন্দেহ। Peep শব্দকে বাংলায় “উঁকিমারা’ বলিতে হয়। Creep শব্দকে “গুঁড়িমারা’ বলিতে হয়। কিন্তু “উঁকিমারা’ “গুঁড়িমারা’ শব্দ ভাবপ্রকাশক হইলেও সর্বত্র ব্যবহারযোগ্য নহে। কারণ উক্ত শব্দগুলিতে আমাদের মনে এমন-সকল ছবি আনয়ন করে যাহার সহিত কোনো মহৎ বর্ণনার যোগসাধন করিতে পারা যায় না।

হিন্দুস্থানী বা মুসলমানদের মধ্যে একটা আদব-কায়দা আছে। একজন হিন্দুস্থানী বা মুসলমান ভৃত্য দিনের মধ্যে প্রভুর সহিত প্রথম সাক্ষাৎ হইবা মাত্রই যে সেলাম অথবা নমস্কার করে তাহার কারণ এমন নহে যে, তাহাদের মনে বাঙালি ভৃত্যের অপেক্ষা অধিক দাস্যভাব আছে, কিন্তু তাহার কারণ এই যে, সভ্যসমাজের সহস্রবিধ সম্বন্ধের ইতিকর্তব্যতা বিষয়ে তাহারা নিরলস ও সতর্ক। প্রভুর নিকটে তাহারা পরিচ্ছন্ন পরিপাটি থাকিবে, মাথায় পাগ্ড়ি পরিবে, বিনীত ভাব রক্ষা করিবে। স্বাভাবিক ভাবে থাকা অপেক্ষা ইহাতে অনেক আয়াস ও শিক্ষা আবশ্যক। আমরা অনেক সময়ে যাহাকে স্বাধীন ভাব মনে করি তাহা অশিক্ষিত অসভ্য ভাব। অনেক সময়ে আমাদের এই অশিক্ষিত ও বর্বর ভাব দেখিয়াই ইংরাজেরা আমাদের প্রতি বীতশ্রদ্ধ হয়, অথচ আমরা মনে মনে গর্ব করি যেন প্রভুকে যথাযোগ্য সম্মান না দেখাইয়া আমরা ভারি একটা কেল্লা ফতে করিয়া আসিলাম। এই অশিক্ষা ও অনাচারবশত আমাদের দৈনিক ভাষা ও কাজের মধ্যে একটি সুমার্জিত সুষমা একটি শ্রী লক্ষিত হয় না। আমরা কেমন যেন “আট-পৌরে’ “গায়েপড়া’ “ফেলাছড়া’ “ঢিলেঢালা’ “নড়বোড়ে’ রকমের জাত, পৃথিবীর কাজেও লাগি না, পৃথিবীর শোভাও সাধন করি না।

The Bengali language and Bengali character: 1

It is often seen that Sanskrit words that are transferred into Bengali express a warped sense of the original meaning; they take on a low, uncivilized form. There is a sense of the mind being affected in the word ‘Ghrina’. It can be used as a synonym for the English words aversion, indignation and contempt. But say the word ‘Ghenna’ and immediately one imagines a malodor invading the nose, an ugly scene unfolding before the eyes and a dirty object being placed near one’s body. There is a pure, generous sense of giving in the Sanskrit word ‘Preeti’, which is sadly lacking in the Bengali ‘Piriti’. I feel ashamed to even use the colloquial Bengali words for ‘Swami’ and ‘Stree’. This will become clear if one compares the Sanskrit ‘Bhorta’ to its Bengali form. I think that the amount of feeling conveyed through the Sanskrit word ‘Lojja’ is greater than that expressed by the Bengali ‘Lojja’. ‘Lojja’ or shame in Bengali is merely a mechanical response, rather than being synonymous with modesty. There is no ‘Hri’ or bashfulness. There is a link between ‘Lojja’ and ‘Shree’ which is missing in Bengali. When there is an instinctive eye for beauty, it is accompanied by a fitting sense of balance in behavior, customs, manner, language, voice and clothing. In Bengali, ‘Lojja’ is something completely separate, it tends to destroy the balance between custom and its application and is overdone to the point of ruining beauty. It is not attained by a gentle unity of body and soul but is more of a purely physical expression.

It is rumoured that Vidyasagar once said that if a hoolock gibbon was to make an idol of Shiva, it would end up fashioning a monkey; the soil of Bengal has a tendency to lend itself to the making of monkeys. It is frequently seen that the aim was to create a Shiva and the result is the creation of a simian. One only has to see what happened to the broadminded religion of love known as Vaishnavism in Bengal over time. Just as there is a need of tremendous mental strength to give birth to a school of great thought, the same strength is essential for its survival. Where sloth and lethargy are part of the culture, great thought soon becomes stunted. There is no effort devoted to its understanding, its maintenance and infusing life into it.

Everything is reduced to a form of slang in our part of the world. I sometimes fear that the great philosophy and teachings of the British will be reduced gradually to a vernacular form in this country. I have seen how many songs become baser in Bengal. I feel that the tunes that are established in civilized countries have a depth to them that allow these to become the national air and express their nationalistic spirit; such as Home Sweet Home and Auld Lang Syne. What do we have in Bengal that has the same ring? The common tunes popular here have no depth or permanence. That is why none of them can be described as national airs. The beauty of the Hindusthani ragas such as Khamaj, Jhinjhit and Kafi is reduced to simple rough tunes such as ‘I am shamed much to go there’ and ‘Tell me why my moonfaced maiden’.

It is not just that; sometimes we feel this division into polite and crude in the difference between Hindusthani and Bengali pronunciation. It is apparent as soon as one tries to break a Hindusthani song into Bengali. Even after retaining the tune and the beat the song sounds very ‘Rotho’. The polite ‘Aa’ of Hindusthani becomes the vulgar ‘Aw’ of Bengali and forces the transformation. The sound ‘Aa’ has a suggestion of detachment while ‘Aw’ merely sounds impoverished and narrow minded. Listening to the Sanskrit spoken in Kashi will make this understanding clear.

I have used the word ‘Rotho’ in the paragraph above in an attempt to say ‘commonplace’. But I felt reluctance to use the word. There are rustic common sounds in all languages. But I have noticed that in Bengali, words that express certain feelings are nothing but rustic. They express the meaning much as a picture does but also convey a meaning that is not quite palatable. One has to say ‘Muchke hashi’ or ‘sneaky smile’ to convey the meaning of ‘Ishodhashyo’ or slight smile in Sanskrit. But the phrase ‘sneaky smile’ awakens a mental picture that is not of a pure smile and certainly not a slight smile. The word ‘peep’ is ‘unkimara’ in Bengali; the word ‘creep’ is ‘gnurimara’. But these two Bengali words are not worthy of using in all situations even though they paint a vivid picture of peeping and creeping as they also seem to imbue these pictures with a vulgar touch that are at odds with their use in any polite accounts.

The Hindi speakers and the Muslims have certain etiquette of behaviour. The fact that a serving man of either persuasion greets his employer with a ‘Namaste’ or a ‘Salaam’ when seeing him for the first time in a day is not because he has more servility in his heart than a Bengali servant does, but because they are conscious and tireless in maintaining the intricacies of each relationship in polite society. They will be clean and well presented in the presence of their employer, they will wear proper dress, and they will be courteous. What we often think of as a spirit of freedom is in reality an expression of poor education and crudity. Often the British are dismissive of us when they see this uneducated and uncivilized side to us but we are secretly proud of having done a great deed by not according our masters the honour they deserve. This has resulted in a lack of polish and beauty in our day to day language and actions. We seem to be a common people who are hangers on, slack, unstable and dispensable; we serve no purpose on this earth nor do we add to its charms.

Image: http://www.thehindu.com/features/magazine/oh-calcutta/article3261359.ece

Swami(husband): Sowami

Stree(wife): Istiri

Bhorta(he who looks after, husband): Bhaataar

You must be logged in to post a comment.