My five year old daughter Mini cannot stay quiet for even one moment. After her arrival on earth, she only took a year to learn how to speak and has not wasted a single waking moment since then in silence. Her mother often scolds her into holding her tongue, but I cannot do that. It is so unnatural to see her when she is not saying something that I cannot bear it for too long. This is why her conversations with me are quite enthusiastic and prolonged.

In the morning I had just started the seventeenth chapter of the novel I am writing, when Mini arrived and started, ‘Baba, the doorman Ramdayal calls a crow Kauwa, he does not know anything. Does he?’

Before I could to enlighten her on the differences between the various languages spoken, she moved on to another topic. ‘See Baba, Bhola was saying that elephants spray water from their trunks in the sky, and that is how it rains. It is amazing what nonsense he can speak! All day and all night, how does he do it?’

Without giving me time to express my views on this either, she suddenly asked me, ‘How are Ma and you related?’

Although I felt like saying she is my wife’s sister, I said aloud, ‘Mini, go and play with Bhola now. I have work to do.’

She then sat down by my feet next to the desk and started playing an animated game of Agdum Bagdum, clapping her own knees with her hands. In my seventeenth chapter, Pratapsinha was about to leap from the high windows of the prison into the fast flowing waters of the river below on a dark night with Kanchanmala clasped to his breast.

My room was by the roadside. Suddenly Mini left her game and ran to the window and started calling loudly, ‘Kabuliwalla, Kabuliwalla.’

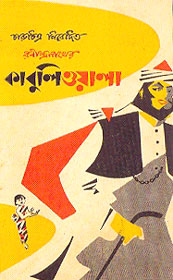

A tall Afghan Kabuliwalla was ambling down the street, wearing loose clothes which were somewhat worse for wear, and a turban. He had a sack slung over his back and carried a couple of boxes of grapes. It is hard to say what Mini thought when she saw him, but she started to call him very loudly. I thought it would be a real problem if this fellow came over with his sack; it would certainly signal an end to my wish of finishing my seventeenth chapter.

But as soon as the man turned his face, smiled at Mini’s calls and started walking towards our house, she ran off into the house at top speed, to be seen no more. She had a firm belief that if one looked into the Kabuliwalla’s sack, a couple of live children were sure to be found.

The Kabuliwalla came and greeted me with a smile – and I thought, even though Pratapsinha and Kanchanmala were in grave danger, it would be rather rude to not buy something from the fellow after calling him.

A few things were bought. Then we talked a bit. The talk revolved around politics, the Russians, the English and the border protection policies.

Finally before leaving he asked, ‘Babu, where did your daughter go?’

I wished to wean Mini off her irrational fear and had her called from inside the house – she stood very close to me and looked suspiciously at the man’s face and the sack. He took some sultanas and prunes out of it and offered them to her. She did not accept them in spite of his entreaties and, doubly suspicious of his gesture, remained hidden behind my knees. The first visit went like this.

One morning a few days later, as I was leaving the house for work, I saw my daughter sitting on a bench near the front door and talking without pause to the Kabuliwalla, who sat at her feet smiling happily and occasionally voicing his opinions in broken Bangla. In her five years of experience Mini had never had such a patient audience apart from her father. I also noticed that her little lap was filled with nuts and raisins. I told the Kabuliwalla, ‘Why have you given her these? Don’t do that any more.’ I then gave him a fifty paise piece which he stowed away in his sack without any hesitation.

When I came home, I found that the fifty paise coin was at the centre of a full scale argument.

Mini’s mother had a shiny white disc in her hand as she questioned Mini in a voice filled with rebuke, ‘Where did you find this?’

Mini explained, ‘The Kabuliwalla gave it to me.’

Her mother asked, ‘Why did you take money from the Kabuliwalla?’

Mini who was very near tears by now said, ‘I did not want it, but he still gave to me.’

I arrived on the scene and rescued Mini from imminent danger and inevitable tears.

I learnt that this was not the second interaction that Mini had had with the Kabuliwalla, he had been coming every day and had conquered a large part of her tiny greedy heart with bribes of pistachio nuts.

I noticed that there were a few words and jokes that were in use between these two friends – such as my daughter’s smiling question as soon as she saw Rahamat, ‘Kabuliwalla, please tell me what you have in that sack of yours?’

To this Rahamat would reply in needlessly nasal tones, ‘Hnati, Elephant!’

There was a subtle sense of the ridiculous in the statement that his sack would hold an elephant. It was not really that subtle, but it amused them both a great deal – and I felt good as I listened to the innocent laughter of two children, one old and one young on those autumn mornings.

There was another thing that was a matter of mirth to the two. Rahamat would say to Mini, ‘Khnoki, wee lass, you should never go to your in-laws’ home!’

Bengali girls are familiar with the term ‘in-laws’ home’ all their lives, but as we were quite modern in our attitudes, we had not informed our little daughter about this place. Thus she could not understand fully what Rahamat meant but to not have a reply ready was foreign to her nature, and she used to ask him in turn, ‘Will you go to your in-laws’ home?’

Rahamat would then shake a huge fist at the imaginary in law and say, ‘Rahamat will beat the in-law soundly first!’

Mini would hear this and laugh a great deal at the thought of this unknown creature’s plight.

It was now autumn and the weather was beautiful. In ancient times kings used to go conquering other lands in this season. I had never gone any where outside Kolkata, but for that very reason my heart would wander the world freely. I was like a traveler forever in my own home; I always missed the places out there. Whenever I heard of foreign places my heart felt drawn to them, similarly when I saw foreigners, my mind conjured a tranquil scene of a river running through a forest, a hut in a clearing and mountains in the distance, and thoughts of a carefree happy existence would spring to mind.

And yet I was of such a lazy disposition that I intensely disliked leaving my familiar corner and going out. This is why the story telling sessions with the Kabuliwalla in the mornings in my little room sitting at my own table satisfied a lot of my yearnings for travel. As he talked in his slow baritone in broken Bangla of his own land, scenes of high mountains on either side of narrow desert tracks, camel caravans loaded with treasures, turbaned riders and men on foot, some armed with spears, others with ancient flint lock muskets floated before my eyes.

Mini’s mother was very easily frightened. A noise on the street was enough to convince her that all the drunks and miscreants in the world were descending on our house. In spite of having lived on this planet for a not inconsiderable period of time, she was constantly fearful that the place was filled with thieves, drunks, snakes, tigers, diseases such as malaria, caterpillars, cockroaches and pesky foreigners.

She was not completely at ease with Rahamat the Kabuliwalla. She had repeatedly asked me to keep a careful eye on him. When I tried to laugh her suspicions away, she asked me a series of questions, ‘Have children never been kidnapped? Is there no slavery in Kabul? Is it totally impossible for a huge Kabuliwalla to steal a small child?’

I had to admit that even though it was not impossible it was unbelievable. Not everyone has the same ability to believe however, and she continued to be afraid of most things. But I could not ask Rahamat to stop coming to our house through no fault of his own.

Every year in winter Rahamat would go home. He was extremely busy collecting his dues at this time. He had to go to many houses but he always came to see Mini once a day. It always seemed like they were conspiring when you saw them together. When he could not make it during the day, I would see him in the evening; to see that tall man in his loose flowing clothes with his huge bag looming up in the darkness was quite a shock at first. But when I saw Mini running to him with cries of ‘Kabuliwalla’ and her face wreathed in smiles, and heard the familiar innocent banter between two friends of disparate ages, my heart was filled with happiness.

One morning I was checking proof sheets in my little room. The last couple of days before winter finally took its leave had been unseasonably cold. The pale winter sun that came through the window and fell on my feet underneath the table felt comfortingly warm. It was probably around eight in the morning – the early risers were returning from their morning walks, wrapped against the weather in mufflers. Suddenly a great uproar was heard on the road.

I looked to see two guardsmen dragging Rahamat along in chains – with a band of curious children in tow. Rahamat’s clothes were bloodstained as was a dagger in the hands of one of his captors. I went outside and asked the men what the matter was.

After speaking to both parties, I managed to find out that one of our neighbours had borrowed money from Rahamat for a Rampuri shawl – he had denied having done this and in the ensuing argument and scuffle Rahamat had stabbed him.

As Rahamat showered the liar with many unmentionable curses, Mini came out calling, ‘Kabuliwalla, Kabuliwalla?’

Rahamat’s face immediately broke into amused smiles. He did not have his sack with him and thus their usual banter could not take place. Mini directly asked him, ‘Will you go to your in-laws’ house?’

Rahamat smiled and said, ‘That is where I am going.’

He realized that Mini did not smile and, showing his bound hands, he said,’I would have beaten him up, but how can I, my hands are tied.’

Rahamat was jailed for a few years for the crime of causing grievous bodily harm.

I forgot about him, in a manner of speaking. While we were spending our days at home in the midst of our familiar daily routine, any thought of how a freedom-loving mountain man was spending years behind prison walls never really occurred to me.

As a father even I have to admit that Mini’s capricious behaviour was very shameful. She forgot her old friend quite easily and made friends with the coachman Nabi. Even later, as she grew older, she made friends with girls rather than with males. She did not even visit her father’s study as much as before. This was a source of much disagreement between the two of us.

Many years have passed since then. Another autumn is here. My Mini’s wedding has been fixed and she will be married during the Puja holidays. Along with the goddess returning to Kailash, the source of happiness in my home will also leave for her in-laws’ home leaving us in darkness.

The morning had started beautifully. The freshly minted autumn sunshine was the colour of liquid gold that had been purified with sulphur. That sunshine had granted an ethereal splendour even on the dreary exposed bricks of untidy crowded houses in our Kolkata alley.

The shehnai flute had started playing in our house as soon as the night ended. That tune seemed to weep from within my ribs. The sad strains of Bhairavi filled the earth with the pain of approaching separation. It is my Mini’s wedding today.

There was a great deal of noise all morning, with the arrival of many people. A cover was being erected on a framework of bamboo, glass shades were being hung in the rooms and verandas with much tinkling of the crystals, and workmen called out loudly to each other all over the house.

As I sat in my study checking accounts, Rahamat came and saluted me.

I did not recognize him at first. His sack was not there. He did not have the long hair of old and his body had lost its sense of pure physical strength. I eventually recognized him by his smile.

I said, ‘How are you, when did you get back?’

He said, ‘I was released from jail yesterday evening.’

The words sounded somewhat incongruous. I had never seen a murderer face to face; my heart seemed to withdraw into itself at his sight. I kept thinking it would be best if this man had just left us alone on this auspicious day.

I said to him, ‘There is a ceremony at home today, and I am a bit busy; you should go now.’

As soon as he heard this he got up to leave. Near the door he paused, and after hesitating a bit, said, ‘Can I not see the wee lass?’

He must have believed Mini was still just the same. It was as though he thought Mini would come running for him, calling, ‘Kabuliwalla, Kabuliwalla’; there would be no change to the old routine of very amusing banter. He had even brought a box of grapes and some dried fruit in a paper bag, possibly borrowed from some friend of his – he no longer had his own supplies.

I said, ‘Today there is a ceremony here, you will not get to meet anyone.’

He seemed a little upset. He looked steadily at me in silence and then saluted me and left the room.

I felt a strange pain. I was thinking of calling him back when I saw him coming back on his own.

He came in and said, ‘I brought these grapes and some dried fruits, please give them to her.’

I took them and started to get some money out to pay for them. He suddenly grabbed my hand and said, ‘You are very kind Sir, I will remember this forever – but do not try to pay me. Sir, just like you have a daughter, I too have a daughter back home. I used to bring dry fruits for your daughter because she reminds me of my child, I have never come for the business.’

Saying this he put his hand into his loose clothing and pulled out a scrap of dirty paper from somewhere near his chest. He unfolded it very carefully and smoothed it onto my table.

I saw a tiny hand print on that piece of paper. Not a photograph or a painting, but a print taken by coating a palm with some soot and pressing it on paper. Rahamat had come to Kolkata every year to sell dried fruits carrying that memento of his daughter – that soft tiny palm touching his saddened heart with sweetness.

My eyes filled with tears at this. I forgot that he was an Afghan fruit seller and that I was a well-to-do Bengali gentleman – I understood that we were both the same, he was a father and so was I. The little hand print of his girl so far from us in her mountain home reminded me of Mini. I instantly sent for her to be brought outside. The womenfolk were not pleased. But I paid no attention to this. Mini shyly came and stood near me dressed in red bridal clothes, her forehead decorated with sandalwood.

Rahamat was startled at first on seeing her, he could not bring back their old camaraderie back. Finally he smiled and said, ‘Khnokhi, little girl, will you go to your in-laws’ home?’

Today Mini understands what the in-laws’ home holds, she could not give him the answer that she had before – she blushed on hearing his question and turned her face away. I remembered the first day the two had met and felt a strange sense of pain.

After Mini had gone Rahamat sighed deeply and sat down on the ground heavily. Suddenly it was clear to him that his own daughter had grown up as well in the mean time – he would have to re-acquaint himself with her – and he would never get the old times back. Who knows what he had gone through in the past eight years! The shehnai flutes played on in the gentle autumn sunshine, as Rahamat sat in an alley in Kolkata and dreamed of a desert in the mountains of Afghanistan.

I took some money and gave it to him. I said, ‘Rahamat, go back to your land and to your daughter; let the joy of that reunion bless Mini’s life.’

As a result of giving this money away I did have to do without a few things I had planned for the celebrations. I could not organize the sort of lighting I had wanted, nor the band I had hoped for and the family was not happy about this; but the light of goodwill brightened the happy ceremony.

You must be logged in to post a comment.