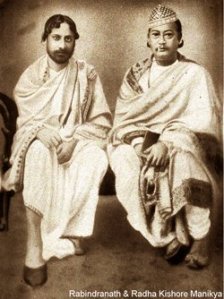

The letters

41 Sakurayama

Nakano, Tokyo

July 23rd, 1938

Dear Rabindranath,

When I visited you at Shantiniketan a few years ago, you were troubled with the Ethiopian question, and vehemently condemned Italy. Retiring into your guest chamber that night, I wondered whether you would say the same thing on Japan, if she were equally situated like Italy. I perfectly agreed with your opinion and admired your courage of speaking, when in Tokyo, 1916, you censured the westernization of Japan from a public platform. Not answering back to your words, the intellectual people of my country were conscious of its possible consequence, for, not only staying as an unpleasant spectacle, the westernization had every chance for becoming anything awful.

But if you take the present war in China for the criminal outcome of Japan’s surrender to the West, you are wrong, because, not being a slaughtering madness, it is, I believe, the inevitable means, terrible it is though, for establishing a new great world in the Asiatic continent, where the “principle of live-and-let-live” has to be realized. Believe me, it is the war of “Asia for Asia.” With a crusader’s determination and with a sense of sacrifice that belongs to a martyr, our young soldiers go to be [the] front. Their minds are light and happy, the war is not for conquest, but the correction of mistaken idea of China, I mean Kuomingtung [Kuomintang] government, and for uplifting her simple and ignorant masses to better life and wisdom. Borrowing from other countries neither money nor blood, Japan is undertaking this tremendous work single-handed and alone. I do not know why we cannot be praised by your countrymen. But we are terribly blamed by them, as it seems, for our heroism and aim.

Sometime ago the Chinese army, defeated in Huntung [Honan] province by Hwangho [Yellow] River, had cut from desperate madness several places of the river bank; not keeping in check the advancing Japanese army, it only made thirty hundred thousand people drown in the flood and one hundred thousand village houses destroyed. Defending the welfare of its own kinsmen or killing them, — which is the object of the Chinese army, I wonder? It is strange that such an atrocious inhuman conduct ever known in the world history did not become in the west a target of condemnation. Oh where are your humanitarians who profess to be a guardian of humanity? Are they deaf and blind? Besides the Chinese soldiers, miserably paid and poorly clothed, are a habitual criminal of robbery, and then an everlasting menace to the honest hard-working people who cling to the ground. Therefore the Japanese soldiers are followed by them with the paper flags of the Rising Sun in their hands; to a soldierly work we have to add one more endeavour in the relief work of them. You can imagine how expensive is this war for Japan. Putting expenditure out of the question, we are determined to use up our last cent for the final victory that would ensure in the future a great peace of many hundred years.

I received the other day a letter from my western friend, denouncing the world that went to Hell. I replied him, saying: “Oh my friend, you should cover your ears, when a war bugle rings too wild. Shut your eyes against a picture of your martial cousins becoming a fish salad! Be patient, my friend, for a war is only spasmodic matter that cannot last long, but will adjust one’s condition better in the end. You are a coward if you are afraid of it. Nothing worthy will be done unless you pass through a severe trial. And the peace that follows after a war is most important.” For this peace we Japanese are ready to exhaust our resources of money and blood.

Today we are called under the flag of “Service-making,” each person of the country doing his own bit for the realization of idealism. There was no time as today in the whole history of Japan, when all the people, from the Emperor to a rag-picker in the street, consolidated together with one mind. And there is no more foolish supposition as that our financial bankruptcy is a thing settled if the war drags on. Since the best part of the Chinese continent is already with us in friendly terms, we are not fighting with the whole of China. Our enemy is only the Kuomingtung government, a miserable puppet of the west. If Chiang Kai-shek wishes a long war, we are quite ready for it. Five years? Ten years? Twenty years? As long as he desires, my friend. Now one year has passed since the first bullet was exchanged between China and Japan; but with a fresh mind as if it sees that the war has just begun, we are now looking the event in the face. After the fall of Hankow, the Kuomingtung government will retire to a remote place of her country; but until the western countries change their attitude towards China, we will keep up fighting with fists or wisdom.

The Japanese poverty is widely advertised in the west, though I do not know how it was started. Japan is poor beyond doubt, — well, according to the measure you wish to apply to. But I think that the Japanese poverty is a fabricated story as much as richness of China. There is no country in the world like Japan, where money is equally divided among the people. Supposing that we are poor, I will say that we are trained to stand the pain of poverty. Japan is very strong in adversity.

But you will be surprised to know that the postal saving of people comes up now to five thousand million yen, responding to the government’s propaganda of economy. For going on, surmounting every difficulty that the war brings in, we are saving every cent and even making good use of waste scraps. Since the war began, we grew spiritually strong and true ten times more than before. There is nothing hard to accomplish to a young man. Yes, Japan is the land of young men. According to nature’s law, the old has to retire while the young advances. Behold, the sun is arising, be gone all the sickly bats and dirty vermins! Cursed be one’s intrigue and empty pride that sin against nature’s rule and justice.

China could very well avoid the war, of course, if Chiang Kai-shek was more sensible with insight. Listening to an irresponsible third party of the west a long way off, thinking too highly of his own strength, he turned at last his own country, as she is today, into a ruined desert to which fifty years would not be enough for recovery. He never happened to think for a moment that the friendship of western countries was but a trick of their monetary interest itself in his country. And it is too late now for Chiang to reproach them for the faithlessness of their words of promise.

For a long time we had been watching with doubt at Chiang’s program, the consolidation of the country, because the Chinese history had no period when the country was unified in the real meaning, and the subjugation of various war-lords under his flag was nothing. Until all the people took an oath of co-operation with him, we thought, his program was no more than a table talk. Being hasty and thoughtless, Chiang began to popularize the anti-Japanese movement among the students who were pigmy politicians in some meaning because he deemed it to be a method for the speedy realization of his program; but he never thought that he was erring from the Oriental ethics that preached on one’s friendship with the neighbours. Seeing that his propagation had too great effect on his young followers, he had no way to keep in check their wild jingoism, and then finally made his country roll down along the slope of destruction. Chiang is a living example who sold his country to the west for nothing, and smashed his skin with the crime of westernization. Dear Rabindranath, what will you say about this Chiang Kai-shek?

Dear poet, today we have to turn our deaf ears towards a lesson of freedom that may come from America, because the people there already ceased to practice it. The ledger-book diplomacy of England is too well known through the world. I am old enough to know from experience that no more worse than others. Though I admit that Japan is today ruled by militarism, natural to the actual condition of the country, I am glad that enough freedom of speaking and acting is allowed to one like myself. Japan is fairly liberal in spite of the war time. So I can say without fear to be locked up that those service-crazy people are drunken, and that a thing in the world, great and true, because of its connection with the future, only comes from one who hates to be a common human unit, stepping aside so that he can unite himself with Eternity. I believe that such a one who withdraws into a snail’s shell for the quest of life’s hopeful future, will be in the end a true patriot, worthy of his own nation. Therefore I am able not to disgrace the name of poet, and to try to live up to the words of Browning who made the Grammarian exclaim:

“Leave Now for dogs and apes! Man has Forever”.

Yours very sincerely,

Yone Noguchi.

Sketch of Noguchi

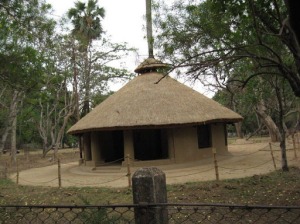

Uttarayan

Santiniketan, Bengal

September 1, 1938

Dear Noguchi,

I am profoundly surprised by the letter that you have written to me: neither its temper nor its contents harmonise with the spirit of Japan which I learnt to admire in your writings and came to love through my personal contacts with you. It is sad to think that the passion of collective militarism may on occasion helplessly overwhelm even the creative artist, that genuine intellectual power should be led to offer its dignity and truth to be sacrificed at the shrine of the dark gods of war.

You seem to agree with me in your condemnation of the massacre of Ethiopia by Fascist Italy but you would reserve the murderous attack on Chinese millions for judgment under a different category. But surely judgments are based on principle, and no amount of special pleading can change the fact that in launching a ravening war on Chinese humanity, with all the deadly methods learnt from the West, Japan is infringing every moral principle on which civilisation is based. You claim that Japan’s situation was unique, forgetting that military situations are always unique, and that pious war-lords, convinced of peculiarly individual justification for their atrocities have never failed to arrange for special alliances with divinity for annihilation and torture on a large scale.

Humanity, in spite of its many failures, has believed in a fundamental moral structure of society. When you speak, therefore, of “the inevitable means, terrible it is though, for establishing a new great world in the Asiatic continent” — signifying, I suppose, the bombing on Chinese women and children and the desecration of ancient temples and Universities as a means of saving China for Asia–you are ascribing to humanity a way of life which is not even inevitable among the animals and would certainly not apply to the East, in spite of her occasional aberrations. You are building your conception of an Asia which would be raised on a tower of skulls. I have, as you rightly point out, believed in the message of Asia, but I never dreamt that this message could be identified with deeds which brought exaltation to the heart of Tamer Lane at his terrible efficiency in manslaughter. When I protested against “Westernisation” in my lectures in Japan, I contrasted the rapacious Imperialism which some of the nations of Europe were cultivating with the ideal of perfection preached by Buddha and Christ, with the great heritages of culture and good neighbourliness that went to the making of Asiatic and other civilisations. I felt it to be my duty to warn the land of Bushido, of great Art and traditions of noble heroism, that this phase of scientific savagery which victimised Western humanity and had led their helpless masses to a moral cannibalism was never to be imitated by a virile people who had entered upon a glorious renascence and had every promise of a creative future before them. The doctrine of “Asia for Asia” which you enunciate in your letter, as an instrument of political blackmail, has all the virtues of the lesser Europe which I repudiate and nothing of the larger humanity that makes us one across the barriers of political labels and divisions. I was amused to read the recent statement of a Tokyo politician that the military alliance of Japan with Italy and Germany was made for “highly spiritual and moral reasons” and “had no materialistic considerations behind them”. Quite so. What is not amusing is that artists and thinkers should echo such remarkable sentiments that translate military swagger into spiritual bravado. In the West, even in the critical days of war-madness, there is never any dearth of great spirits who can raise their voice above the din of battle, and defy their own warmongers in the name of humanity. Such men have suffered, but never betrayed the conscience of their peoples which they represented. Asia will not be westernised if she can learn from such men: I still believe that there are such souls in Japan though we do not hear of them in those newspapers that are compelled at the cost of their extinction to reproduce their military master’s voice.

“The betrayal of intellectuals” of which the great French writer spoke after the European war, is a dangerous symptom of our Age. You speak of the savings of the poor people of Japan, their silent sacrifice and suffering and take pride in betraying that this pathetic sacrifice is being exploited for gun running and invasion of a neighbour’s hearth and home, that human wealth of greatness is pillaged for inhuman purposes. Propaganda, I know, has been reduced to a fine art, and it is almost impossible for peoples in non-democratic countries to resist hourly doses of poison, but one had imagined that at least the men of intellect and imagination would themselves retain their gift of independent judgment. Evidently such is not always the case; behind sophisticated arguments seem to lie a mentality of perverted nationalism which makes the “intellectuals” of today to blustering about their “ideologies” dragooning their own “masses” into paths of dissolution. I have known your people and I hate to believe that they could deliberately participate in the organised drugging of Chinese men and women by opium and heroin, but they do not know; in the meanwhile, representatives of Japanese culture in China are busy practising their craft on the multitudes caught in the grip of an organisation of a wholesale human pollution. Proofs of such forcible drugging in Manchukuo and China have been adduced by unimpeachable authorities. But from Japan there has come no protest, not even from her poets.

Holding such opinions as many of your intellectuals do, I am not surprised that they are left “free” by your Government to express themselves. I hope they enjoy their freedom. Retiring from such freedom into “a snail’s shell” in order to savour the bliss of meditation “on life’s hopeful future”, appears to me to be an unnecessary act, even though you advise Japanese artists to do so by way of change. I cannot accept such separation between an artist’s function and his moral conscience. The luxury of enjoying special favouritism by virtue of identity with a Government which is engaged in demolition, in its neighbourhood, of all salient bases of life, and of escaping, at the same time, from any direct responsibility by a philosophy of escapism, seems to me to be another authentic symptom of the modern intellectual’s betrayal of humanity. Unfortunately the rest of the world is almost cowardly in any adequate expression of its judgment owing to ugly possibilities that it may be hatching for its own future and those who are bent upon doing mischief are left alone to defile their history and blacken their reputation for all time to come. But such impunity in the long run bodes disaster, like unconsciousness of disease in its painless progress of ravage.

I speak with utter sorrow for your people; your letter has hurt me to the depths of my being. I know that one day the disillusionment of your people will be complete, and through laborious centuries they will have to clear the debris of their civilisation wrought to ruin by their own warlords run amok. They will realise that the aggressive war on China is insignificant as compared to the destruction of the inner spirit of chivalry of Japan which is proceeding with a ferocious severity. China is unconquerable, her civilisation, under the dauntless leadership of Chiang Kai-shek, is displaying marvelous resources; the desperate loyalty of her peoples, united as never before, is creating a new age for that land. Caught unprepared by a gigantic machinery of war, hurled upon her peoples, China is holding her own; no temporary defeats can ever crush her fully aroused spirit. Faced by the borrowed science of Japanese militarism which is crudely western in character, China’s stand reveals an inherently superior moral stature. And today I understand more than ever before the meaning of the enthusiasm with which the big-hearted Japanese thinker Okakura [Kakuzo or Tenshin] assured me that China is great.

You do not realise that you are glorifying your neighbour at your own cost. But these are considerations on another plane: the sorrow remains that Japan, in the words of Madame Chiang Kai-shek which you must have read in the Spectator, is creating so many ghosts. Ghosts of immemorial works of Chinese art, of irreplaceable Chinese institutions, of great peace-loving communities drugged, tortured, and destroyed. “Who will lay the ghosts [to rest]?” she asks. Japanese and Chinese people, let us hope, will join hands together, in no distant future, in wiping off memories of a bitter past. True Asian humanity will be reborn. Poets will raise their song and be unashamed, one believes, to declare their faith again in a human destiny which cannot admit of a scientific mass production of fratricide.

Yours sincerely,

Rabindranath Tagore

PS I find that you have already released your letter to the press; I take it that you want me to publish my answer in the same manner.

Sketch of Tagore

41, Sakurayama

Nakano, Tokyo

Oct. 2nd, 1938

Dear Tagore,

Your eloquent letter, dated Sept. 1st. was duly received. I am glad that the letter inspired me to write you once more.

No one in Japan denies the greatness of China, — I mean the Chinese people. China of the olden times was great with philosophy, literature and art, — particularly in the T’ang dynasty. Under Chinese influence Japan started to build up her own civilization. But I do not know why we should not oppose to the misguided government of China for the old debt we owe her people. And nobody in Japan ever dreams that we can conquer China. What Japan is doing in China, it is only, as I already said, to correct the mistaken idea of Chiang Kai-shek; on this object Japan in staking her all. If Chiang Kai-shek [alters his course]; on this object Japan is staking her hands for the future of both the countries, China and Japan, the war will be stopped to once.

I am glad that you still admire Kakuzo Okakura with enthusiasm as a thinker. If he lives to-day, I believe that he will say the same thing as I do. Betraying your trust, many Chinese soldiers in the front surrender to our Japanese force, and join with us in the cry, “Down with Chiang Kai-shek!” Where is Chinese loyalty to him?

Having no proper organ of expression, Japanese opinion is published only seldom in the west; and real fact is always hidden and often camouflaged by cleverness of the Chinese who are a born propagandist. They are strong in foreign languages, and their tongues never fail. While the Japanese are always reticent, even when situation demands their explanation. From the experiences of many centuries, the Chinese have cultivated an art of speaking for they had been put under such a condition that divided their country to various antagonistic divisions; and being always encroached by the western countries, they depended on diplomacy to turn a thing to their advantage. Admitting that China completely defeated Japan in foreign publicity, it is sad that she often goes too far and plays trickery. For one instance I will call your attention to the reproduced picture from a Chinese paper on page 247 of the Modern Review for last August, as a living specimen of “Japanese Atrocities in China: Execution of a Chinese Civilians.” So awful pictures they are — awful enough to make ten thousand enemies of Japan in a foreign country. But the pictures are nothing but a Chinese invention, simple and plain, because the people in the scenes are all Chinese, slaughterers and all. Besides any one with commonsense would know, if he stops for a moment, that it is impossible to take such a picture as these at the front. Really I cannot understand how your friend-editor of the modern Review happened to published them.

It is one’s right to weave a dream at the distance, and to create an object of sympathy at the expense of China. Believe me that I am second to none in understanding the Chinese masses who are patient and diligent, clinging to the ground. But it seems that you are not acquainted with the China of corruption and bribery, and of war lords who put money in a foreign bank when their country is at stake. So long as the country is controlled by such polluted people, the Chinese have only a little chance to create a new age in their land. They have to learn first of all the meaning of honesty and sacrifice before dreaming it. But for this new age in Asia, Japan is engaging in the war, hoping to obtain a good result and mutual benefit that follow the swords. We must have a neighbouring country, strong and true, which is glad to co-operate with us in our work of reconstructing Asia in the new way. That is only what we expect from China.

Japan’s militarism is a tremendous affair no doubt. But if you condemn Japan, because of it, you are failing to notice that Chiang’s China is a far more great military country than Japan. China is now mobilizing seven or eight million soldiers armed with European weapons. From cowardice or being ignorant of the reason why they had to fight, the Chinese soldiers are so unspirited in the front. But for this unavailability you cannot forgive Chiang’s militarism, if your denial is absolute and true. For the last twenty years Chiang had been trying to arm his country under the western advisers; and these western advisers were mostly from Italy and Germany, the countries of which you are so impatient. And it should be attributed to their advice that he started war; though it is too late to blame the countries that formally provided him with military knowledge, it is never too late for him to know that the western countries are not worthy of trust. There is no country in the world that comes to rescue the other at her own expense. If you are a real sympathizer of China, you should come along with your program what she has to do, not passing idly with your condemnation of Japan’s militarism. And if you have to condemn militarism, that condemnation should be equally divided between China and Japan.

It is true that when two quarrel, both are in the wrong. And when fighting is over, both the parties will be put perhaps in the mental situation of one who is crying over spilt milk. War is situation of one who is crying over spilt milk. War is atrocious, — particularly when it is performed in a gigantic way as in China today. I hope that you will let me apply your accusation of Japanese atrocity to China, just as it is. Seeing no atrocity in China, you are speaking about her as an innocent country. I expected something impartial from a poet.

I have to thank you that you called my attention to the “Modern intellectual’s betrayal of humanity,” whatever it be. One can talk any amount of idealism, apart from in reality, if he wishes, and take the pleasure of one belonging to no country. But sharing patriotism equally with the others, we are trying to acquit the duty of talk [of] Heaven when immediate matter of the earth is well arranged.

Supposing that we accept your advice to become a vanguard of humanity according to your prescription, and supposing that we leave China to her own will, and save ourselves from being a “betrayal of the intellectuals,” who will promise us with the safety of Japanese spirit that we cultivated with pairs of thousand years, under the threat of communism across a fence? We don’t want to barter our home land for an empty name of intellectuals. No, you mustn’t talk nonsense! God forbid!

Admitting, that militarism is criminal, I think that, if your humanity makes life a mutilated mud-fish, its crime would never be smaller than the other. I spent my whole life admiring beauty and truth, with one hope to lift life to a dignity, more vigorous and noble; from this reason, I face in madness, with three wild eyes, promised me with a forthcoming peace. And also at Elephanta Island; near Bombay, I learned from the Three-headed Siva a lesson of destruction as inevitable truth of life. Then I wrote:

“Thy slaughter’s sword is never so unkind as it appears.

Creation is great, but destroying is still greater,

Because up from the ashes new Wonder take its flight.”

But if you command me to obey the meekness of humanity under all the circumstances, you are forgetting what your old Hindu philosophy taught you. I say this not only for my purpose, because such reflection is important for any country.

I wonder who reported to you that we are killing innocent people and bombing on their unprotected towns. Far from it, we are trying to do our best for helping them, because we have so much to depend on them for co-operation in the future, and because Bushido command us to limit punishment to a thing which only deserves it. It was an apt measure of our Japanese soldiers that the famous cave temples of the 5th century in North China were saved from savage rapacity of the defeated Chinese soldiers in fight. Except Madame Chiang with frustrated brain, no one has seen the “ghosts of Chinese institutions and art, destroyed”. And if those institutions and art, admitting that they are immemorial and irreplaceable, had been ever destroyed it is but the crazy work of Chinese soldiers, because they want to leave a desert to Japan. You ought to know better since you are acquainted with so many Japanese, whether or not we are qualified to do anything barbarous.

I believe that you are versed in Bushido. In olden time soldiery was lifted in Japan to a status equally high as that of art and morality. I have no doubt that our soldiers will not betray and tradition. If there is difference in Japanese militarism from that of the west, it is because the former is not without moral element. Who only sees its destroying power is blind to its other power in preservation. Its human aspect is never known in the foreign countries, because they shut their eyes to it. Japan is still an unknown existence in the west. Having so many things to displease you, Japanese militarism has still something that will please you if you come to know more about it. It is an excusable existence for the present condition of Japan. But I will leave the full explanation of it to some later occasion.

Believe me that I am never a eulogist of Japanese militarism, because I have many differences with it. But I can not help accepting as a Japanese what Japan is doing now under the circumstances, because I see no other way to show our minds to China. Of course when China stops fighting, and we receive her friendly hands, neither grudge nor ill feeling will remain in our minds. Perhaps with some sense of repentance, we will then proceed together on the great work of reconstructing the new world in Asia.

I often draw in my mind a possible man who can talk from a high domain and act as a peace-maker. You might write General Chiang, I hope, and tell him about the foolishness of fighting in the presence of a great work that is waiting. And I am sorry that against the high-pitched nature of your letter, mine is low-toned and faltering, because as a Japanese subject I belong to one of the responsible parties of the conflict.

Finally one word more. What I fear most is the present atmosphere in India, that tends to willfully blacken Japan to alienate her from your country. I have so many friends there, whose beautiful nature does not harmonise with it. My last experiences in your country taught me how to love and respect her. Besides there are in Japan so many admirers of your countrymen with your noble self as the first.

Yours sincerely,

Yone Noguchi.

Uttarayana

Santiniketan, Bengal

October, 1938

Dear Noguchi,

I thank you for taking the trouble to writer to me again. I have also read with interest your letter addressed to the Editor, Amrita Bazar Patrika, and published in that journal.* It makes the meaning of your letter to me more clear.

* The following is the text of the letter referred to:

Dear Editor,

Dr. Tagore’s reply to my letter was a disappointment, to use his words, hurted me to the depths of my being. Now I am conscious that language is an ineffective instrument to carry one’s real meaning. When I wanted an impartial criticism he gave me something of prejudiced bravado under the beautiful name of humanity. Just for a handful of dream, and for an intellectual’s ribbon to stick in his coat, he has lost a high office to correct the mistaken idea of reality.

It seems to us that when Dr. Tagore called the doctrine of “Asia for Asia” a political blackmail, he relinquished his patriotism to boast quiescence of a spiritual vagabond, and willfully supporting the Chinese side, is encouraging Soviet Russia, not to mention the other western countries. I meant my letter to him to be a plea for the understanding of Japan’s view-point which, in spite of its many failures, is honest. I wonder whether it is a poet’s privilege to give one whipping before listening to his words. When I dwelled on the saving of the people of Japan at the present time of conflict, he denounced it as their government’s exploitation “for gun running and invasion of a neighbour’s hearth and home.” But when he does not use the same language towards his friend China his partiality is something monstrous. And I wonder where is his former heart which made us Japanese love him and honour him. But still we are patient, believing that he will come to senses and take a neutral dignity fitting to a prophet who does not depart from fair judgment.

“Living in a country far from your country, I do not know where Dr. Tagore’s reply appeared in print. Believing that you are known to his letter, I hope that you will see way to print this letter of mine in your esteemed paper.

Yours sincerely,

Yone Noguchi.”

I am flattered that you still consider it worthwhile to take such pains to convert me to your point of view, and I am really sorry that I am unable to come to my senses, as you have been pleased to wish it. It seems to me that it is futile for either of us to try to convince the other since your faith in the infallible right of Japan to bully other Asiatic nations into line with your Government’s policy is not shared by me, and my faith that patriotism which claims the right to bring to the altar of its country the sacrifice of other people’s rights and happiness will endanger rather than strengthen the foundation of any great civilization, is sneered at by you as the “quiescence of a spiritual vagabond”.

If you can convince the Chinese that your armies are bombing their cities and rendering their women and children homeless beggars — those of them that are not transformed into “mutilated mud-fish”, to borrow one of your own phrases –, if you can convince these victims that they are only being subjected to a benevolent treatment which will in the end “save” their nation, it will no longer be necessary for you to convince us of your country’s noble intentions. Your righteous indignation against the “polluted people” who are burning their own cities and art treasures (and presumably bombing their own citizens) to malign your soldiers, reminds me of Napoleon’s noble wrath when he marched into a deserted Moscow and watched its palaces in flames. I should have expected from you who are a poet at least that much of imagination to feel, to what inhuman despair a people must be reduced to willingly burn their own handiwork of years’, indeed centuries’, labour. And even as a good nationalist, do you seriously believe that the mountain of bleeding corpses and the wilderness of bombed and burnt cities that is every day widening between your two countries, is making it easier for your two peoples to stretch your hands in a clasp of ever-lasting good will?

You complain that while the Chinese, being “dishonest”, are spreading their malicious propaganda, you people, being “honest”, are reticent. Do you not know, my friend, that there is no propaganda like good and noble deeds, and that if such deeds by yours, you need fear no “trickery” of your victims? Nor need you fear the bogey of communism if there is no exploitation of the poor among your own people and the workers feel that they are justly treated.

I must thank you for explaining to me the meaning of our Indian philosophy and of pointing out that the proper interpretation of Kali and Shiva must compel our approval of Japan’s “dance of death” in China. I wish you had drawn a moral from a religion more familiar to you and appealed to the Buddha for your justification. But I forget that your priests and artists have already made sure of that, for I saw in a recent issue of “The Osaka Mainichi and The Tokyo Nichi Nichi” (16th September, 1938) a picture of a new colossal image of Buddha erected to bless the massacre of your neighbours.

You must forgive me if my words sound bitter. Believe me, it is sorrow and shame, not anger, that prompt me to write to you. I suffer intensely not only because the reports of Chinese suffering batter against my heart, but because I can no longer point out with pride the example of a great Japan. It is true that there are no better standards prevalent anywhere else and that the so-called civilized peoples of the West are proving equally barbarous and even less “worthy of trust.” If you refer me to them, I have nothing to say. What I should have liked is to be able to refer them to you. I shall say nothing of my own people, for it is vain to boast until one has succeeded in sustaining one’s principles to the end.

I am quite conscious of the honour you do me in asking me to act as a peace-maker. Were it in any way possible for me to bring you two peoples together and see you freed from this death-struggle and pledged to the great common “work of reconstructing the new world in Asia”, I would regard the sacrifice of my life in the cause a proud privilege. But I have no power save that of moral persuasion, which you have so eloquently ridiculed. You who want me to be impartial, how can you expect me to appeal to Chiang Kai-shek to give up resisting until the aggressors have first given up their aggression? Do you know that last week when I received a pressing invitation from an old friend of mine in Japan to visit your country, I actually thought for a moment, foolish idealist as I am, that your people may really need my services to minister to the bleeding heart of Asia and to help extract from its riddled body the bullets of hatred? I wrote to my friend:

“Though the present state of my health is hardly favourable for any strain of a long foreign journey, I should seriously consider your proposal if proper opportunity is given me to carry out my own mission while there, which is to do my best to establish a civilised relationship of national amity between two great peoples of Asia who are entangled in a desolating mutual destruction. But as I am doubtful whether the military authorities of Japan, which seem bent upon devastating China in order to gain their object, will allow me the freedom to take my own course, I shall never forgive myself if I am tempted for any reason whatever to pay a friendly visit to Japan just at this unfortunate moment and thus cause a grave misunderstanding. You know I have a genuine love for the Japanese people and it is sure to hurt me too painfully to go and watch crowds of them being transported by their rulers to a neighbouring land to perpetrate acts of inhumanity which will brand their name with a lasting stain in the history of Man.”

After the letter was despatched came the news of the fall of Canton and Hankow. The cripple, shorn of his power to strike, may collapse, but to ask him to forget the memory of his mutilation as easily as you want me to, I must expect him to be an angel.

Wishing you people whom I love, not success, but remorse,

Yours sincerely,

Rabindranath Tagore

http://www.japanfocus.org/-Zeljko-Cipris/2577/article.html

You must be logged in to post a comment.