১৪

আশা জিজ্ঞাসা করিল, “সত্য করিয়া বলো, আমার চোখের বালিকে কেমন লাগিল।”

মহেন্দ্র কহিল, “মন্দ নয়।”

আশা অত্যন্ত ক্ষুণ্ন হইয়া কহিল, “তোমার কাউকে আর পছন্দই হয় না।”

মহেন্দ্র। কেবল একটি লোক ছাড়া।

আশা কহিল, “আচ্ছা, ওর সঙ্গে আর-একটু ভালো করিয়া আলাপ হউক, তার পরে বুঝিব, পছন্দ হয় কি না।”

মহেন্দ্র কহিল, “আবার আলাপ! এখন বুঝি বরাবরই এমনি চলিবে।”

আশা কহিল, “ভদ্রতার খাতিরেও তো মানুষের সঙ্গে আলাপ করিতে হয়। একদিন পরিচয়ের পরেই যদি দেখাশুনা বন্ধ কর, তবে চোখের বালি কী মনে করিবে বলো দেখি। তোমার কিন্তু সকলই আশ্চর্য। আর কেউ হইলে অমন মেয়ের সঙ্গে আলাপ করিবার জন্য সাধিয়া বেড়াইত, তোমার যেন একটা মস্ত বিপদ উপস্থিত হইল।”

অন্য লোকের সঙ্গে তাহার এই প্রভেদের কথা শুনিয়া মহেন্দ্র ভারি খুশি হইল। কহিল, “আচ্ছা, বেশ তো। ব্যস্ত হইবার দরকার কী। আমার তো পালাইবারস্থান নাই, তোমার সখীরও পালাইবার তাড়া দেখি না– সুতরাং দেখা মাঝে মাঝে হইবেই, এবং দেখা হইলে ভদ্রতা রক্ষা করিবে, তোমার স্বামীর সেটুকু শিক্ষা আছে।”

মহেন্দ্র মনে স্থির করিয়া রাখিয়াছিল, বিনোদিনী এখন হইতে কোনো-না-কোনো ছুতায় দেখা দিবেই। ভুল বুঝিয়াছিল। বিনোদিনী কাছ দিয়াও যায় না– দৈবাৎ যাতায়াতের পথেও দেখা হয় না।

পাছে কিছুমাত্র ব্যগ্রতা প্রকাশ হয় বলিয়া মহেন্দ্র বিনোদিনীর প্রসঙ্গ স্ত্রীর কাছে উত্থাপন করিতে পারে না। মাঝে মাঝে বিনোদিনীর সঙ্গলাভের জন্য স্বাভাবিক সামান্য ইচ্ছাকেও গোপন ও দমন করিতে গিয়া মহেন্দ্রের ব্যগ্রতা আরো যেন বাড়িয়া উঠিতে থাকে। তাহার পরে বিনোদিনীর ঔদাস্যে তাহাকে আরো উত্তেজিত করিতে থাকিল।

বিনোদিনীর সঙ্গে দেখা হইবার পরদিনে মহেন্দ্র নিতান্তই যেন প্রসঙ্গক্রমে হাস্যচ্ছলে আশাকে জিজ্ঞাসা করিল, “আচ্ছা, তোমার অযোগ্য এই স্বামীটিকে চোখের বালির কেমন লাগিল।”

প্রশ্ন করিবার পূর্বেই আশার কাছ হইতে এ সম্বন্ধে উচ্ছ্বাসপূর্ণ বিস্তারিত রিপোর্ট পাইবে, মহেন্দ্রের এরূপ দৃঢ় প্রত্যাশা ছিল। কিন্তু সেজন্য সবুর করিয়া যখন ফল পাইল না, তখন লীলাচ্ছলে প্রশ্নটা উত্থাপন করিল।

আশা মুশকিলে পড়িল। চোখের বালি কোনো কথাই বলে নাই। তাহাতে আশা সখীর উপর অত্যন্ত অসন্তুষ্ট হইয়াছিল।

স্বামীকে বলিল, “রোসো, দু-চারি দিন আগে আলাপ হউক, তার পরে তো বলিবে। কাল কতক্ষণেরই বা দেখা, ক’টা কথাই বা হইয়াছিল।”

ইহাতেও মহেন্দ্র কিছু নিরাশ হইল এবং বিনোদিনী সম্বন্ধে নিশ্চেষ্টতা দেখানো তাহার পক্ষে আরো দুরূহ হইল।

এই-সকল আলোচনার মধ্যে বিহারী আসিয়া জিজ্ঞাসা করিল, “কী মহিনদা, আজ তোমাদের তর্কটা কী লইয়া।”

মহেন্দ্র কহিল, “দেখো তো ভাই, কুমুদিনী না প্রমোদিনী না কার সঙ্গে তোমার বোঠান চুলের দড়ি না মাছের কাঁটা না কী একটা পাতাইয়াছেন, কিন্তু আমাকেও তাই বলিয়া তাঁর সঙ্গে চুরোটের ছাই কিংবা দেশালাইয়ের কাঠি পাতাইতে হইবে, এ হইলে তো বাঁচা যায় না।”

আশার ঘোমটার মধ্যে নীরবে তুমুল কলহ ঘনাইয়া উঠিল। বিহারী ক্ষণকাল নিরুত্তরে মহেন্দ্রের মুখের দিকে চাহিয়া হাসিল– কহিল, “বোঠান, লক্ষণ ভালো নয়। এ-সব ভোলাইবার কথা। তোমার চোখের বালিকে আমি দেখিয়াছি। আরো যদি ঘন ঘন দেখিতে পাই, তবে সেটাকে দুর্ঘটনা বলিয়া মনে করিব না, সে আমি শপথ করিয়া বলিতে পারি। কিন্তু মহিনদা যখন এত করিয়া বেকবুল যাইতেছেন তখন বড়ো সন্দেহের কথা।”

মহেন্দ্রের সঙ্গে বিহারীর যে অনেক প্রভেদ, আশা তাহার আর-একটি প্রমাণ পাইল।

হঠাৎ মহেন্দ্রের ফোটোগ্রাফ-অভ্যাসের শখ চাপিল। পূর্বে সে একবার ফোটোগ্রাফি শিখিতে আরম্ভ করিয়া ছাড়িয়া দিয়াছিল। এখন আবার ক্যামেরা মেরামত করিয়া আরক কিনিয়া ছবি তুলিতে শুরু করিল। বাড়ির চাকর-বেহারাদের পর্যন্ত ছবি তুলিতে লাগিল।

আশা ধরিয়া পড়িল, চোখের বালির একটা ছবি লইতেই হইবে।

মহেন্দ্র অত্যন্ত সংক্ষেপে বলিল, “আচ্ছা।”

চোখের বালি তদপেক্ষা সংক্ষেপে বলিল, “না।”

আশাকে আবার একটা কৌশল করিতে হইল এবং সে কৌশল গোড়া হইতেই বিনোদিনীর অগোচর রহিল না।

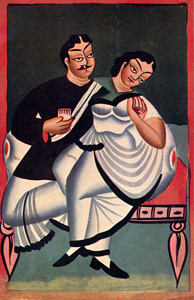

মতলব এই হইল, মধ্যাহ্নে আশা তাহাকে নিজের শোবার ঘরে আনিয়া কোনোমতে ঘুম পাড়াইবে এবং মহেন্দ্র সেই অবস্থায় ছবি তুলিয়া অবাধ্য সখীকে উপযুক্তরূপ জব্দ করিবে।

আশ্চর্য এই, বিনোদিনী কোনোদিন দিনের বেলায় ঘুমায় না। কিন্তু আশার ঘরে আসিয়া সেদিন তাহার চোখ ঢুলিয়া পড়িল। গায়ে একখানি লাল শাল দিয়া খোলা জানালার দিকে মুখ করিয়া হাতে মাথা রাখিয়া এমনই সুন্দর ভঙ্গিতে ঘুমাইয়া পড়িল যে মহেন্দ্র কহিল, “ঠিক মনে হইতেছে, যেন ছবি লইবার জন্য ইচ্ছা করিয়াই প্রস্তুত হইয়াছে।”

মহেন্দ্র পা টিপিয়া টিপিয়া ক্যামেরা আনিল। কোন্ দিক হইতে ছবি লইলে ভালো হইবে, তাহা স্থির করিবার জন্য বিনোদিনীকে অনেকক্ষণ ধরিয়া নানাদিক হইতে বেশ করিয়া দেখিয়া লইতে হইল। এমন-কি, আর্টের খাতিরে অতি সন্তর্পণে শিয়রের কাছে তাহার খোলা চুল এক জায়গায় একটু সরাইয়া দিতে হইল– পছন্দ না হওয়ায় পুনরায় তাহা সংশোধন করিয়া লইতে হইল। আশাকে কানে কানে কহিল, “পায়ের কাছে শালটা একটুখানি বাঁ দিকে সরাইয়া দাও।”

অপটু আশা কানে কানে কহিল, “আমি ঠিক পারিব না, ঘুম ভাঙাইয়া দিব– তুমি সরাইয়া দাও।”

মহেন্দ্র সরাইয়া দিল।

অবশেষে যেই ছবি লইবার জন্য ক্যামেরার মধ্যে কাচ পুরিয়া দিল, অমনি যেন কিসের শব্দে বিনোদিনী নড়িয়া দীর্ঘনিশ্বাস ফেলিয়া ধড়ফড় করিয়া উঠিয়া বসিল। আশা উচ্চৈঃস্বরে হাসিয়া উঠিল। বিনোদিনী বড়োই রাগ করিল– তাহার জ্যোতির্ময় চক্ষু দুইটি হইতে মহেন্দ্রের প্রতি অগ্নিবাণ বর্ষণ করিয়া কহিল, “ভারি অন্যায়।”

মহেন্দ্র কহিল, “অন্যায়, তাহার আর সন্দেহ নাই। কিন্তু চুরিও করিলাম, অথচ চোরাই মাল ঘরে আসিল না, ইহাতে যে আমার ইহকাল পরকাল দুই গেল! অন্যায়টাকে শেষ করিতে দিয়া তাহার পরে দণ্ড দিবেন।”

আশাও বিনোদিনীকে অত্যন্ত ধরিয়া পড়িল। ছবি লওয়া হইল। কিন্তু প্রথম ছবিটা খারাপ হইয়া গেল। সুতরাং পরের দিন আর-একটা ছবি না লইয়া চিত্রকর ছাড়িল না। তার পরে আবার দুই সখীকে একত্র করিয়া বন্ধুত্বের চিরনিদর্শনস্বরূপ একখানি ছবি তোলার প্রস্তাবে বিনোদিনী “না’ বলিতে পারিল না। কহিল, “কিন্তু এইটেই শেষ ছবি।”

শুনিয়া মহেন্দ্র সে ছবিটাকে নষ্ট করিয়া ফেলিল। এমনি করিয়া ছবি তুলিতে তুলিতে আলাপ পরিচয় বহুদূর অগ্রসর হইয়া গেল।

14

Asha asked, ‘Tell me honestly, how did you like my best friend?’

Mahendra conceded, ‘She is not bad.’

Asha was very mortified, ‘You don’t know how to appreciate anyone.’

Mahendra: Except for one person.

Asha said, ‘Well, once you get to know her a bit, I will ask you if you still feel this way about her.’

Mahendra said, ‘Get to know her? Are we to do this thing regularly from now on?’

Asha answered, ‘One meets people if only for the sake of propriety. If you stop seeing her just after a day, what do you think she will think? You are really strange, you know that? If it was any other man, they would be eager to meet a woman like her, and you act as if it is a huge hassle!’

Mahendra was rather excessively pleased to find this difference between him and others. He said, ‘Oh well, there is no hurry then, is there? I have nowhere to run to, your friend too shows no sign of going anywhere soon – so we will meet occasionally, and if we do, I will behave politely, even I know that much!’

Mahendra had assumed that Binodini would now appear before him frequently on the flimsiest of excuses. But he was wrong about her. She completely avoided him; he never saw her while he was leaving home or going about the house.

He could not raise the topic with his wife for fear that of giving away his eagerness to see her friend. Somehow the fact that he felt he had to hide even a natural interest in Binodini’s company seemed to make him want to see her even more. Her disinterest fuelled his desire even more.

The day after he met Binodini, he asked Asha very casually as an aside, ‘So, what did your friend think of this undeserving husband of yours?’

He had firmly expected that Asha would give him a detailed and enthusiastic report on the subject without him asking. But when he waited in vain without hearing from her, he asked the question with a show of nonchalance.

Asha was in a fix. Her friend had actually said nothing. This made Asha very annoyed.

She said to her husband, ‘Wait, once you talk to her a couple more times, she will be able to say something about you. After all, yesterday you met for such a short while, you barely spoke two words to each other!’

Mahendra was a bit disappointed at this; in addition, it had the effect of making it even harder for him to remain ambivalent about Binodini.

Bihari arrived in the midst of this conversation and asked, ‘What are you two arguing about today?’

Mahendra said, ‘Your sister –in-law has established some kind of ‘hair tie’ or ‘herring bone’ relationship with some one called Kumudini or Promodini; but does that mean I will now have to call her endearing names too, like ‘cheroot ash’ or ‘match stick’? This is quite beyond me!’

Asha grew flustered in silent protest behind her veil. Bihari looked at Mahendra for a while without saying anything and then said with a smile, ‘Sister–in–law, this does not bode well. These are all excuses. I have seen your Chokher Bali. I can swear that if I did see her more regularly there is no way I would have considered that a mishap. But I am very suspicious to see that Mahendra is protesting so much.’

This was another proof that Mahendra was very different from everyone else, including Bihari, Asha thought.

Mahendra suddenly developed a keen interest in taking photographs. He had once started to learn photography before but had quickly tired of it. This time he even got his camera fixed and bought the chemicals needed to develop the prints before starting to take photographs of everyone, even the domestic staff at home.

Asha requested Mahendra to take one photograph of Binodini.

Mahendra said in short, ‘Yes.’

Binodini answered with even more economy, ‘No.’

Asha had to think up another plan and this time again Binodini was completely aware of the scheme as soon as Asha thought of it.

The plan was that Asha would entice her to her own bedroom and somehow put her to sleep upon which Mahendra would take a photograph of her and they would have their revenge.

The astonishing thing was that Binodini who never ever took day time naps, came to Asha’s room that very day and fell fast asleep. She slept so prettily, her face turned to the window with her arm framing it, a red shawl wrapped about her that Mahendra said, ‘She looks just as if she was readying herself to be photographed!’

Mahendra tiptoed about, setting up the camera. He had to look at Binodini from various angles for a long time in order to decide on the best aspect from which to take his photo. In fact, purely for the sake of art, he even had to go really close to her to move her flowing hair to one side and then re-adjust it. He then whispered to Asha, ‘Can you move her shawl so that it drapes to the left of her feet?’

Asha who did not trust herself whispered back, ‘I won’t be able to do it without waking her up, you do it!’

So Mahendra moved it.

Eventually just as he inserted a glass plate in the camera, Binodini stirred with a sigh and sat up suddenly at some sound. Asha laughed out aloud. Binodini was furious and her blazing eyes rained reproach on Mahendra saying, ‘This is so wrong!’

Mahendra said, ‘I have behaved very wrongly without doubt. But if I have done anything wrong, I might as well have something to show for that. You can punish me after that if you want to.’

Asha insisted too that Binodini would have to have her photo taken. It was taken. But the first shot was ruined. The photographer insisted on another photo the next day. Binodini could not refuse the offer to have her friendship with Asha caught in another photograph for posterity after that was taken. But she said, ‘This is the very last one!’

Mahendra destroyed the photo when he heard this. In this manner, through frequent photography sessions the two became very familiar with each other.

You must be logged in to post a comment.